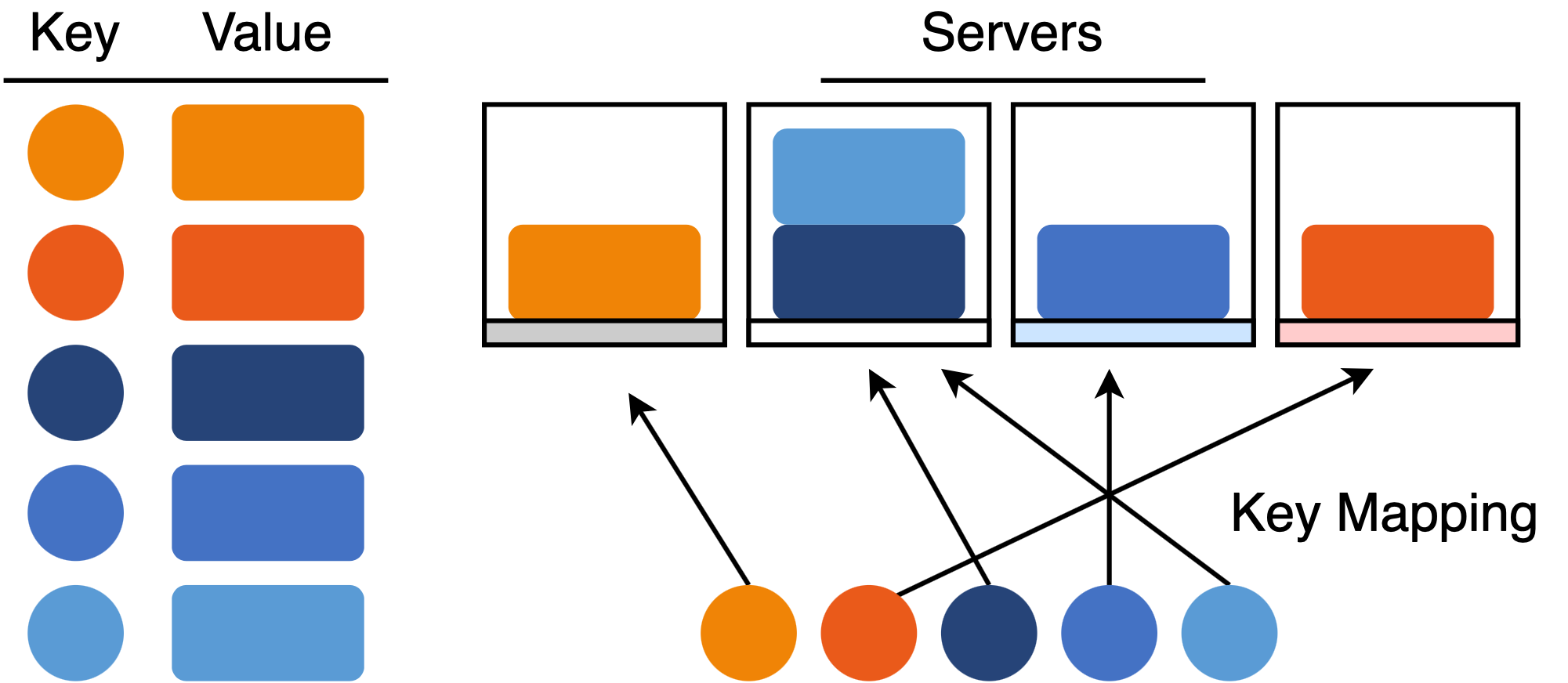

Rendezvous hashing is an algorithm to solve the distributed hash table problem - a common and general pattern in distributed systems. There are three parts of the problem:

- Keys: unique identifiers for data or workloads

- Values: data or workloads that consume resources

- Servers: entities that manage data or workloads

For example, in a distributed storage system, the key might be a filename, the value is the file data, and the servers are networked data servers that collectively store all of the files. Given a key and a dynamic list of servers, the task is to map keys to servers while preserving:

- Load Balancing: Each server is responsible for (approximately) the same number of loads.

- Scalability: We can add and remove servers without too much computational effort.

- Lookup Speed: Given a key, we can quickly identify the correct server.

The set of servers is dynamic in the sense that we are allowed to add or remove servers at any time during the operation of the system.

Introduction to Rendezvous Hashing

When confronted with a load balancing problem, most engineers will pick an algorithm based on consistent hashing. Rendezvous hashing is much less well-known, despite being older than consistent hashing and providing different technical advantages. Why is this so?

The simple answer is that computer science courses often cover consistent hashing without introducing rendezvous hashing, but I think there is a deeper underlying reason for the popularity difference. In 1999, Akamai Technologies hosted the ESPN March Madness games and the movie trailer for Star Wars: The Phantom Menace. The trailer was so popular that the traffic crashed the film studio’s website - Akamai’s webcaches were the only way to access the video for several days. This event generated substantial public interest in Akamai, and the core component of Akamai’s content delivery network was consistent hashing. Then, the 2007 DynamoDB paper from Amazon touted consistent hashing as an integral part of Amazon’s successful commercial database. I suspect that rendezvous hashing is less popular because it never had the same kind of “killer app” moments.

However, rendezvous hashing is far from obsolete - engineering teams have quietly used the algorithm with great success since 1996. In fact, there seems to be a renewed interest in rendezvous hashing as an alternative to consistent hashing. Consistent hashing trades load balancing for scalability and lookup speed, but rendezvous hashing provides an alternative tradeoff that emphasizes equal load balancing. Over the last few years, rendezvous hashing has re-emerged as a good algorithm to load balance medium-size distributed systems, where an \(O(N)\) lookup cost is not prohibitive.

Why is it called “Rendezvous Hashing”? The motivation of the original 1996 paper was to provide a way for a data provider to communicate data to a client through a proxy server. To exchange the data, the client and provider meet - or rendezvous - at a selected proxy server. Rendezvous hashing is a distributed way for the client and provider to mutually agree on the meeting location.

Rendezvous Hashing Algorithm

The goal of rendezvous hashing is to have good load balancing performance - we want each server to be responsible for about the same number of key-value pairs. One reasonable way to make this happen is for each key to select a server uniformly at random, just like with an ordinary hash table. The trick is that if we simply hash the keys to the servers, all of the hash values change when we modify the number of servers.

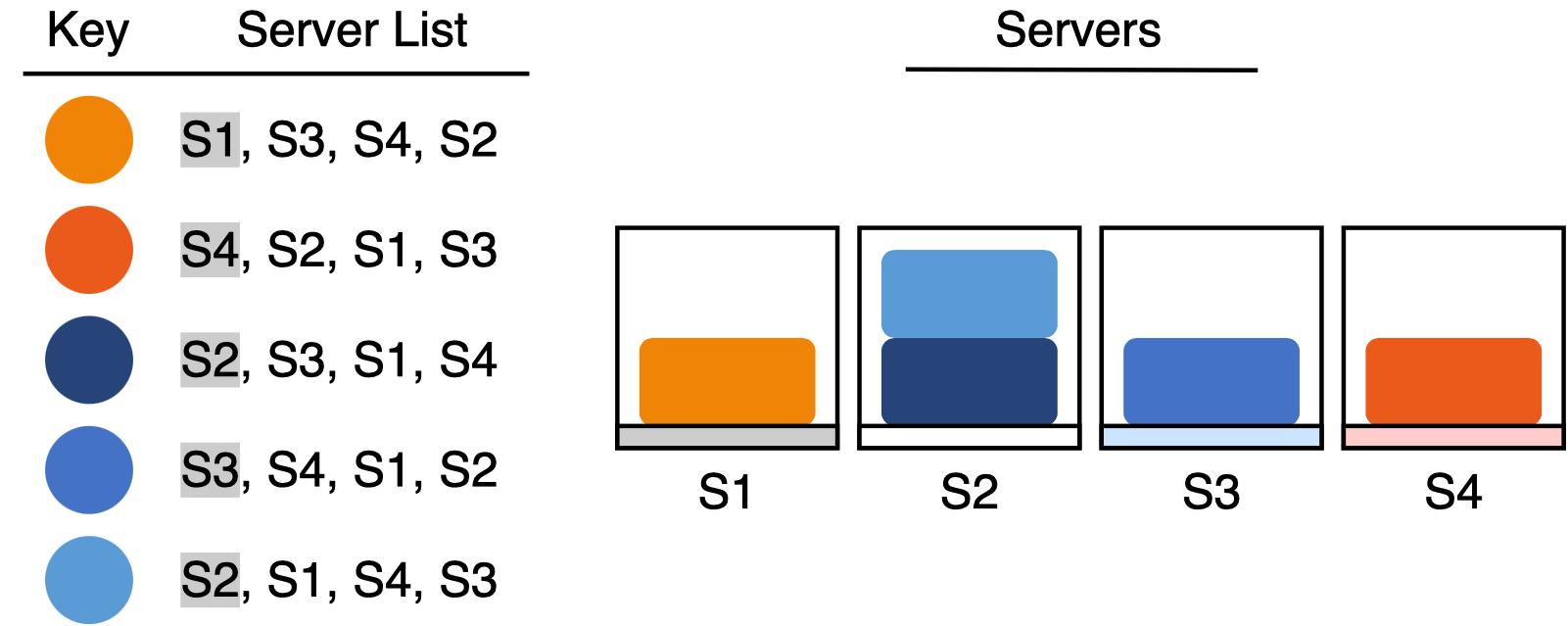

Rendezvous hashing provides a clever solution. Rather than pick a single server, each key generates a randomly sorted list of servers and chooses the first server from the list. To guarantee a successful lookup, we must ensure that each key-value pair is managed by the key’s first server choice. I call this property the “first choice” invariant.

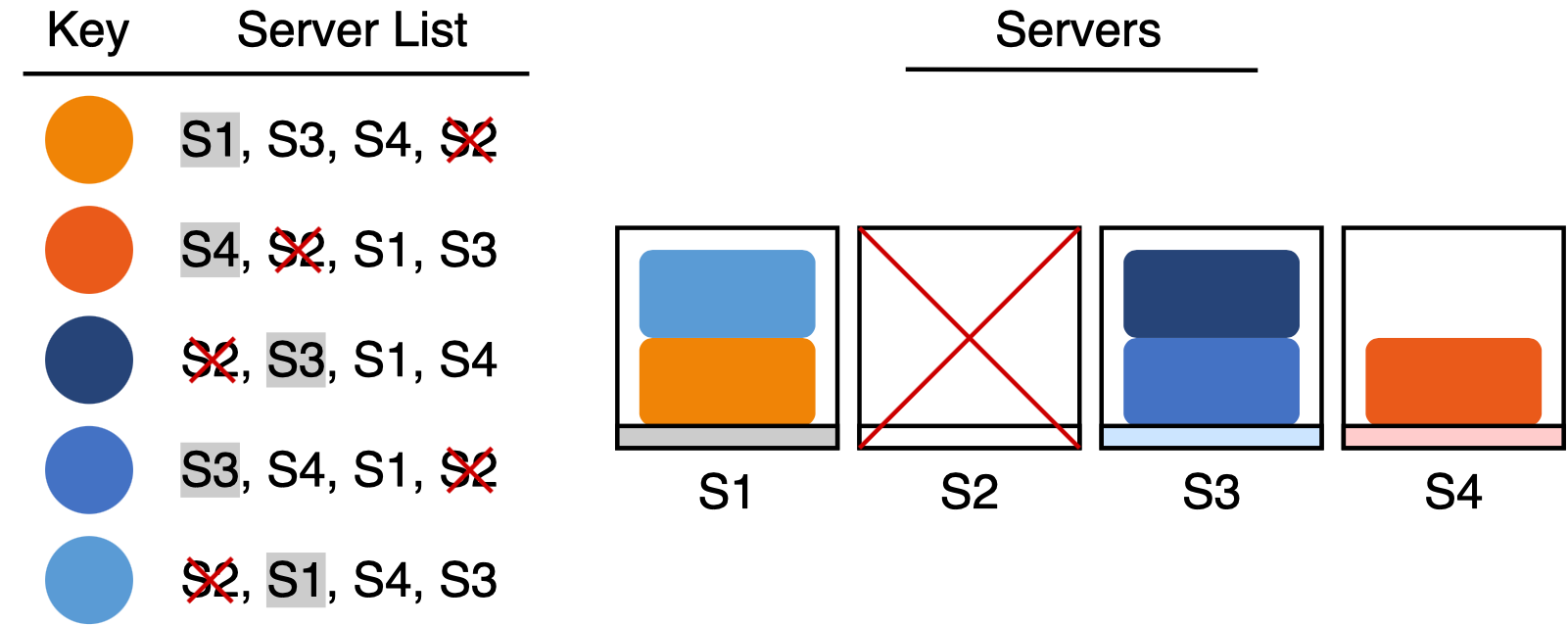

If our first choice for a server goes offline, we simply move the key to the second server in the list (which becomes our new first choice). It is easy to see that we only need to move the keys that were previously managed by the server that went offline. The rest of the keys do not need to move, since they are still managed by their first choice. For example, if we were to delete server S2 in the example, the items in S2 would move to their new first choices: S1 and S3. None of the other items have to move though, since S2 wasn’t their first choice.

One Weird Hashing Trick

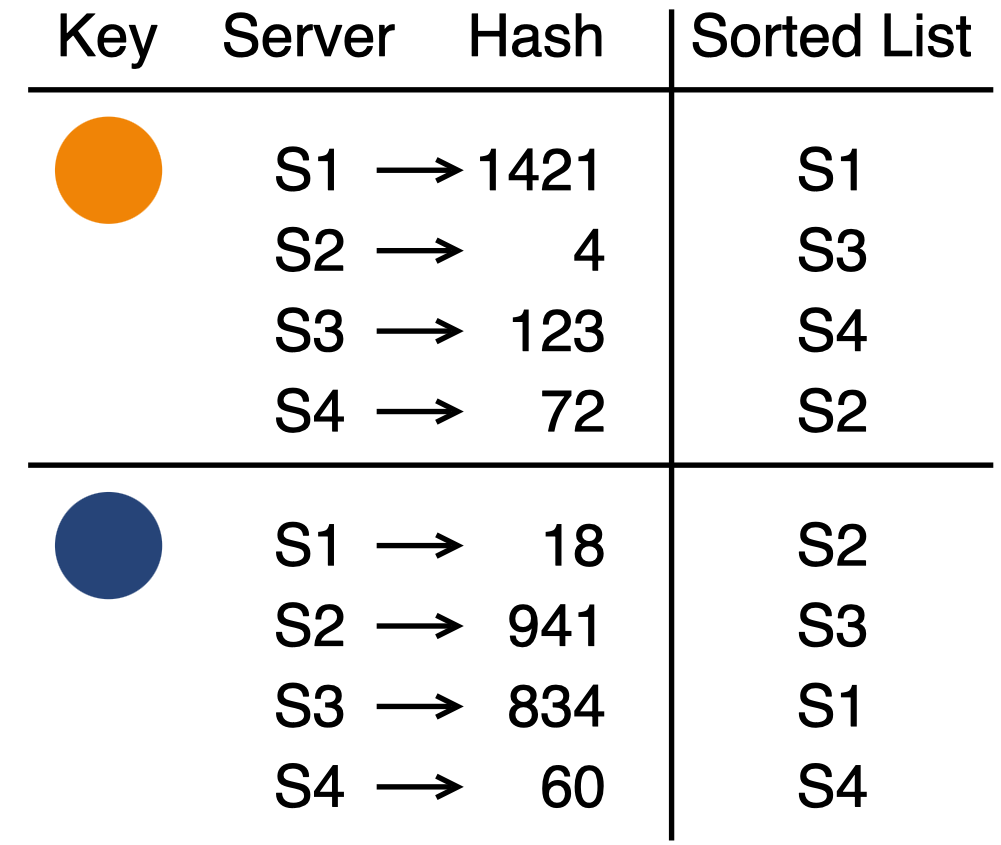

To use rendezvous hashing, each key needs its own unique server priority list. How do we generate a random permutation of servers for each key?

It turns out that we can directly apply a common hashing technique to permute a set of items.1 First, we hash each server to get a set of integer hash values. Then, we sort the servers based on the hash values. The result is a randomly permuted list of servers. To ensure that each key gets a unique permutation, we also have to make the hash function depend on the key. But this is not difficult - the solution is to concatenate the key with each server or to use the server ID as a hash seed.

The final rendezvous hashing algorithm goes like this:

- Hash all possible key-server combinations with a random hash function

- Assign the key to the server with the largest hash value

- Maintain the “first choice” invariant when adding and removing servers

Advantages of Rendezvous Hashing

Cascaded Failover: When a server fails, many load balancing algorithms forward all of the load to a single server. This can lead to cascaded failure if the failover server cannot handle the new load. Rendezvous hashing avoids this problem because each key potentially has a different second-choice server. With a sufficiently good hash function,2 the load from a failing server is evenly distributed across the remaining servers.

Weighted Servers: In some situations, we want to do biased load balancing rather than uniform random key assignment. For example, some servers might have larger capacity and should therefore be selected more often. Rendezvous hashing accommodates weighted servers in a very elegant way. Instead of sorting the servers based on their hash values, we rank them based on \(-\frac{w_i}{\ln h_i(x)}\), where \(x\) is the key, \(w_i\) is the weight associated with server \(i\), and \(h_i(x)\) is the hash value (normalized to [0,1]). For more details, see Jason Resch’s slides from SDC 2015.

Lightweight Memory: We only need a list of server identifiers to locate the server that manages a given key-value pair, since we can locally compute all of the hash function values. In practice, algorithms such as consistent hashing require more memory (but less computation).

Disadvantages of Rendezvous Hashing

Adding Servers: It is hard to maintain the “first choice” invariant when adding servers because the new server might become the first choice for a key that is already in the system. To maintain the invariant, we would have to verify that all of the keys in the system are managed by the correct server. This is a serious problem for distributed storage and pub/sub systems because they route users to resources that are distributed throughout the system. If we break the invariant, we break the ability to locate resources (values) in the system.

However, this is not a problem for cache systems. In a cache system, users access data through fast, local servers that have shared access to a slow central data storage repository. When a user requests data from the system, we query the cache to see whether a local copy is available. If the cache doesn’t have a copy, we fetch the data from the central repository and cache it for next time.

We do not have to worry about adding servers to a cache because the system will eventually satisfy the “first choice” invariant by itself. If we add a server that becomes the first choice for an existing key, the new server will simply load the corresponding data after the first unsuccessful cache request. Now that the new server is responsible for the key, the old server that previously managed the key will no longer receive any more requests for the data. Since most caches evict data on an LRU (least recently used) basis, we will eventually flush any stale data copies from the system. This effectively implements the “first choice” invariant without requiring any effort.

Query Time: If we have \(N\) servers, the lookup algorithm is \(O(N)\) because we have to examine all of the key-server combinations. Consistent hashing is \(O(\log N)\) and can be much faster when \(N\) is large enough.

Conclusion

Rendezvous hashing is a good way to do distributed load balancing for small to medium-sized distributed caches. If working with a system that does not eventually satisfy the “first choice” invariant, rendezvous hashing will require some care when scaling up the number of servers.

Notes

-

The same trick is used to implement MinHash, a locality sensitive hash function. ↩

-

My intuition is that the hash function has to be 2-universal for this to be true, but I did not check. \ ↩