Randomized algorithms are a pain to develop. If done right, they can seriously improve performance and cut compute costs. But they can also produce some of the most counterintuitive and frustrating bugs ever. I’ve found that certain design patterns and testing methods work better than others - here are some practical tips that make things easier.

The advice applies to programs that behave randomly, which includes some machine learning algorithms and many randomized data structures. Please do not apply the advice to cryptographic programs unless you wish to create a horrible privacy disaster.

Where is the randomness?

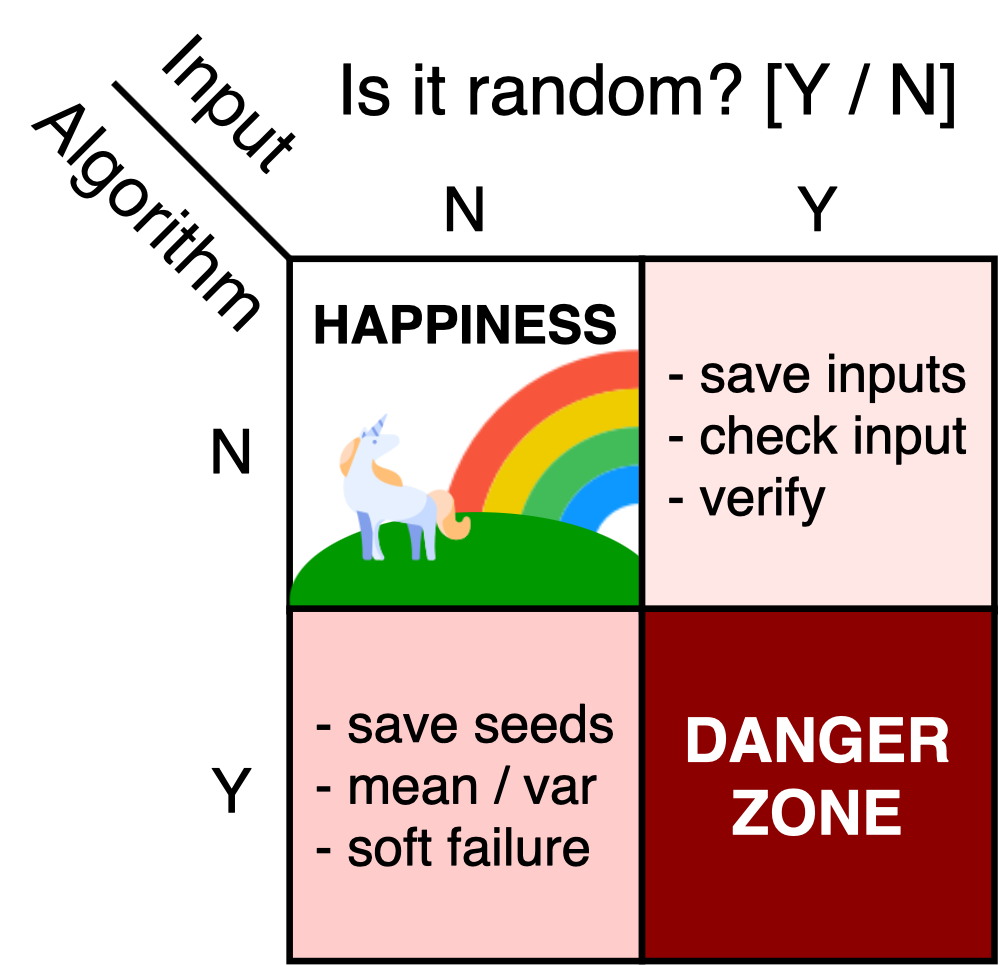

Your job may be easier or harder based on what parts of the program are random. I mentally distinguish between four flavors of random:

-

Normal input, normal code: This is the easiest type - too bad it’s an endangered species. If your application doesn’t involve machine learning or interacting with humans, it might live here. Keep in mind that your program might interact with something random - such as a machine learning API - but that is okay as long as you are not strongly coupled with the random component. Stepping through the code with a debugger is usually enough to catch mistakes.

-

Random input, normal code: Lots of signal processing methods and some of the simpler machine learning algorithms fall into this category - we apply a fixed algorithm to randomly generated inputs. It is good practice to record properties of the input and output such as the mean and variance. Placing “sanity check” filters on all the inputs and outputs will help prevent lots of problems. It’s also a good idea to save the input data when the program fails.

-

Normal input, random code: This category includes randomized solutions for clearly defined problems, such as sorting or nearest neighbor search. Some randomized algorithms can return many different outputs for the same input, so we need to save both the random seed and the input data.

-

Random input, random code: I call this the danger zone because it’s not easy to figure out whether a bug came from a bad input, a bug in the randomized algorithm, or a “perfect storm” style interaction between the user, the input, and the random number generator. Since real-world inputs are pretty random, most machine learning code falls in the danger zone.

Monte Carlo vs Las Vegas: Some people also draw a distinction between Monte Carlo algorithms and Las Vegas algorithms. Monte Carlo algorithms are guaranteed to run fast but might fail to solve the problem. Las Vegas algorithms are guaranteed to solve the problem but might run slow. I am aware of two ways to get a Las Vegas algorithm. The first way is to use a random number of steps to output the correct answer. The second way is to have a fast method to check whether the output is correct. In the second case, we can guess and check with a Monte Carlo method until we get lucky and have a correct output.

I think that Monte Carlo algorithms are harder to implement than Las Vegas algorithms. If your Las Vegas algorithm fails, congratulations - you’ve found a bug. If your Monte Carlo algorithm fails, you might have found a bug. You might also have just gotten unlucky. We will focus on Monte Carlo algorithms, but you can replace “correct program output” with “fast runtime” if that is a better fit for your situation.

Random Number Generators

Nearly all random programs use pseudorandom number generators (PRNG) to simulate a random algorithm. The PRNG generates a long, periodic sequence of numbers that appear to be random. The generator starts with a random seed that determines which sequence of numbers we get. These numbers are sufficiently random for most applications, but cryptography and privacy are the exceptions to the rule. To use randomness for security, we need to use true random numbers at some point in the algorithm and be extra careful with random seeds.1 The advice in this section does not necessarily apply to cryptographic applications.

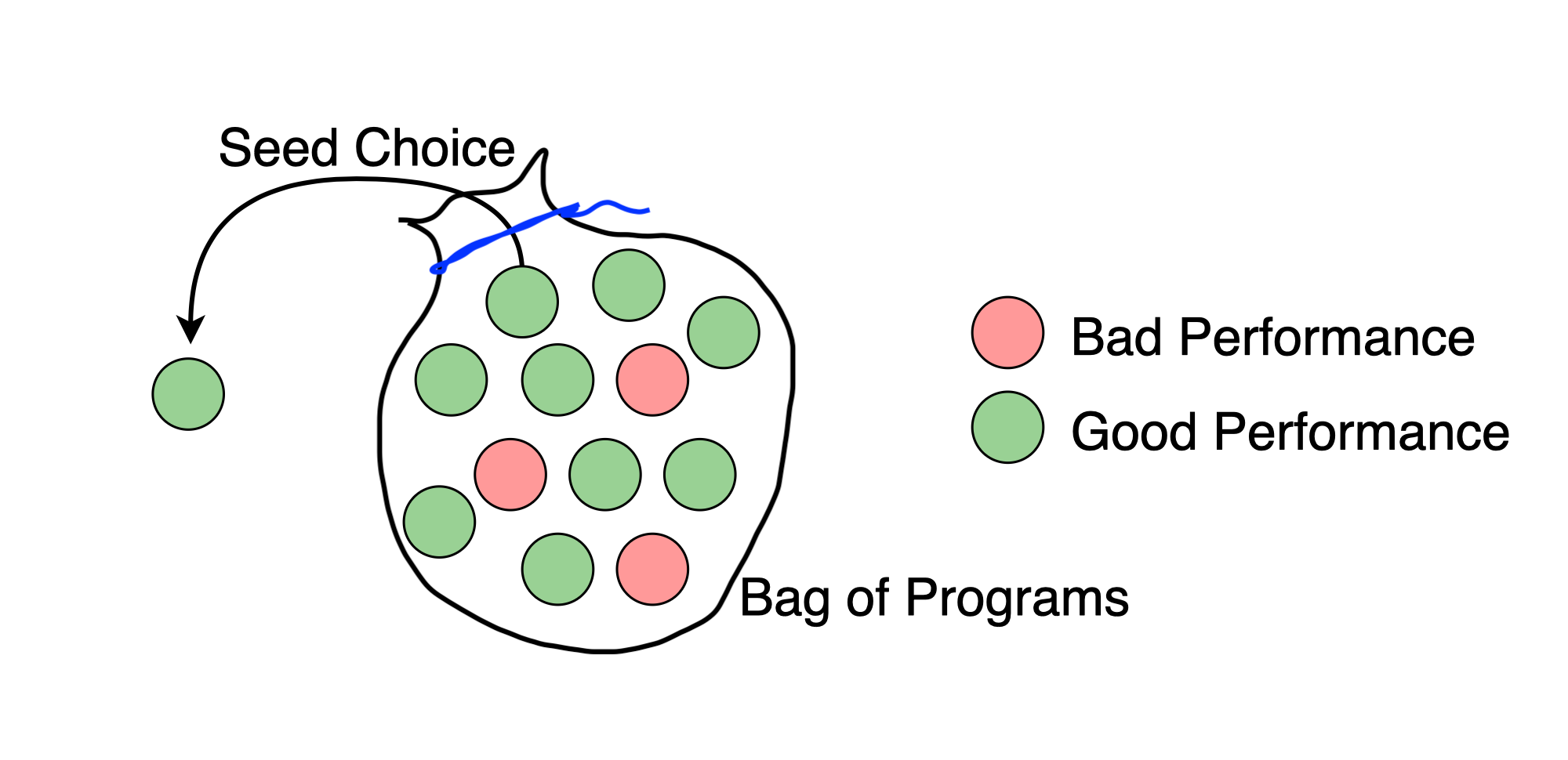

For development purposes, you can think of a randomized algorithm as a bag of deterministic programs. Some of these programs have good performance, but a few do not. When we select a random seed, we are effectively picking one of the programs from the bag. We might get unlucky and accidentally pick a bad program, but most randomized algorithms have guarantees that say this does not happen too often. This is a simplified view of pseudorandomness, but it provides good intuition in practice.2

Once we have chosen a random seed, the behavior of the program should be completely reproducible. This has some important practical consequences.

1. Take the seed as a parameter

Every randomized function or class should take a seed as an optional parameter with a random default value. The random number generator is part of the internal state of the program, and it is impossible to reproduce bugs without the ability to set this state.

I have experienced a large amount of pain from hardcoded random seeds. All new team members should sign a pledge that says you won’t hardcode random seeds, enforceable via git blame. If you don’t provide a way to set the seed, someone will inevitably go spelunking through your code, digging for the buried seeds and possibly breaking things.

2. Save the random seeds

A general rule of thumb is that a class should have a random seed member whenever it owns a PRNG or stores data generated by a PRNG. If you serialize the class or save the output of a random program, save the seed as well.

3. Seed values are important

Aleksey Bilogur did a large-scale analysis of all the code hosted by GitHub and found that 75% of all random seeds are either 0, 1 or 42. This is simultaneously ridiculous and also not surprising at all. To understand why this is a problem, think about our bag of programs from earlier. By restricting our attention to just three choices, we may be throwing away many of the programs with the best performance. PRNG seeding is even more critical for security applications. Cryptographically secure seeding is beyond the scope of this post, but see this whitepaper for an introduction.

4. Different algorithms need different generators

If two random elements are unrelated, they should have separate generators. This is not for theoretical reasons - it is mathematically acceptable to use the same generator for all the randomness in the program, even for multiple independent random variables. However, two objects that share a random number generator are coupled in deep and mysterious ways.

For example, suppose that we use a random number generator to construct an object. If we later use the same generator with a different object, the behavior of the second object depends on the arguments to the first object’s constructor! This results in reproducibility bugs that are nearly impossible to track down. A good rule of thumb is for each class instance to have its own generator.

5. Different algorithms need different seeds

If the data processing pipeline involves more than one PRNG, the random seeds should be chosen independently. Suppose we use the same random seed everywhere. Events that were previously unlikely, such as two unrelated variables having the same value, are now very likely to happen, introducing complicated dependencies and failure modes. The implementation might still run, but perhaps not as well. Theoretical performance guarantees are usually only valid for independent random sources.

6. Random seeds are read-only

If we switch to using a different random seed halfway through the execution of the program, the program’s behavior is no longer reproducible. While there are valid reasons to re-seed a generator, you may need to consider a second PRNG if you find yourself resetting the generator often.

Program Design

Good design is especially important for randomized programs.3 Here are some guidelines that go beyond the generic principles of encapsulation and abstraction.

1. Quarantine the randomness

There should be a clear separation between the randomized parts of the system and everything else. You should protect users by hiding the randomness behind a stable well-designed API. Make the interface as airtight as possible so that the randomness does not escape and spread chaos to other parts of the codebase. Even though random algorithms are unpredictable, external users should be able to trust the output of the program. To improve trust, you might use:

- sanity checks that the output is within a valid range of allowable output values

- validity checks on the input and output of a module

- theoretical guarantees that the algorithm satisfies a certain performance requirement

I usually build one class for each randomized thing in my code. The algorithms are only allowed to interact with the outside world via a clearly-defined class interface that has as few parameters as possible. Each class has its own internal PRNG and a private seed that can only be set once, during construction. I have seen code that allows the user to bring their own RNG, but I think this exposes too many details. Different PRNGs have different performance tradeoffs. For instance, cryptographically secure PRNGs are too slow for physics simulations but are critical for security programs. You are more likely to make an informed choice than the user.

2. Bring your own seeds

Allow the state of the PRNG to be controlled up to the highest level possible. Testing and development are much easier if we can completely derandomize the behavior of the program. All external or top-level interfaces should have completely reproducible behavior once a random seed is specified. If you have more than one random number generator, resist the urge to use the same random seed everywhere. Instead, create a configuration structure that contains all the random seeds. A serialized version of this structure can form a unique global seed, if necessary.

3. Limit the scope of randomness

Many parts of a randomized algorithm are likely to be deterministic. A hash table might access random locations, but the lookup process is always the same once the location is known. Deterministic routines should be extracted from the random parts of the program so that the unpredictability is restricted to a few clearly-labeled locations.

4. Prefer random inputs over random implementation

It is better to write deterministic modules that take random inputs than to write random modules that take deterministic inputs. By rearranging the code, we can de-randomize our programs and move them out of the danger zone. Many algorithms work by randomly annotating the data and then applying a fixed processing step. For example, hash tables annotate inputs with a hash value and process them with a table lookup. Data-parallel machine learning algorithms annotate data points with a compute node and process them with SGD. One class could be responsible for both annotation and processing, but it is better to separate the implementations so that the randomness is limited to the scope of the annotator.

Testing and Bugs

Randomized programs have more bugs than normal programs. Normal programs have ordinary deterministic bugs. Randomized programs have those too, but they also have sneaky stochastic bugs. Stochastic bugs are like landmines that only detonate when your random seed is a multiple of 17. If none of your tests cover that specific case, you won’t even know there’s a bug.

Usually, we find bugs with tests. But testing a randomized program is hard because the output changes each time we run the program. This prevents us from simply testing whether the program outputs the right answer, since a correct program might output many different answers. For instance, the Count-Min sketch outputs a count value that is guaranteed to be close to the true value, but any integer value within the error bound is a correct output.

Testing is also hard because many randomized algorithms are occasionally allowed to fail. If we test the program and observe a failure, it is hard to say whether the program failed because it was incorrectly implemented or because the algorithm just happened to fail that time.

1. Locating problems

Even if we test the program many times and observe more failures than expected, it is not easy to tell if the problem is with the algorithm or with the implementation. It is hard to distinguish between a bug that increases the number of program failures and a bad algorithm that fails often. A reliable reference implementation of the algorithm is the best diagnostic tool for this kind of issue. If the reference code is correct and you standardize the random seeds, then you can locate bugs by finding places where your program behaves differently than the reference code. You can also use theoretical guarantees to verify whether the program is correct. If the theory claims that the performance should be much better than your observations, there is likely a bug. If you have neither theory nor a reference implementation, the only option is to carefully check the code step-by-step.

For example, I once wrote a randomized graph search program that made a larger number of edge traversals than the reference implementation. The underlying cause of the problem was that my code re-examined some (but not all) nodes that had already been visited. Without the reference implementation, I might never have known that this bug existed. I found and fixed the bug by making corrections until the two implementations visited exactly the same nodes.

2. De-randomize the program

Do you remember the “bag of programs” analogy, where setting the random seed is the same as drawing a program from the bag? Once we choose a program, we can debug it like any normal deterministic program. Some bugs might affect all the programs in the bag, while others might only affect a fraction of the bag. Therefore, it is important to repeat the tests with several different random seeds.

3. Measure correctness via statistics

Since the performance can change from run to run, it is important to measure aggregate statistics over many runs to assess performance. For an algorithm with clear failure criteria, you might report the percentage of times that the algorithm fails. For a situation where errors can differ in magnitude, you might report the average error on a benchmark task with a known solution. It is essential to report confidence intervals or standard deviations along with the summary statistics. This allows us to design tests with soft failure conditions. If a code change causes a performance regression larger than two standard deviations, the change probably includes a bug.

4. Stress tests

You should brutally stress-test your algorithm. Run the program with lots of different random seeds, and keep the seeds that cause the program to fail. Check to see whether the failure modes share suspicious underlying characteristics. Measure key statistics at various places in the program and compare their distributions for failed runs and successful runs. I try to run the program at least 1000 times during a stress test.

5. Mock out components

If your randomized system is complex and has many strongly coupled parts, you may want to debug each part individually. The simplest way to do this is to save the intermediate output from each component and use the saved version when running your tests. It is also worthwhile to try synthetic inputs that are at the extreme ranges of the inputs you expect.

Notes

-

For cryptographically secure applications, we need true random numbers. True entropy can be collected from various sources and then used to seed a cryptographically secure PRNG - David Wagner at Berkeley has a nice list of ways to harvest truly random numbers for those who are interested. ↩

-

A rigorous mathematical discussion of pseudorandomness can be found here. ↩

-

I started thinking about the problem of developing randomized algorithms when I worked at Aventusoft, where we used signal processing algorithms on random inputs. We had code to check the inputs, but the program would crash if the check failed. I spent a lot of time chasing down failures by mocking out components and saving inputs to isolate specific problems. These guidelines were further refined by experiences during my PhD (where I worked on all sorts of randomized things) and my time at Amazon (where I worked on universal hash functions). ↩