Big data, machine learning and the Internet of Things all face a similar problem: limited computer resources. This might be surprising - we expect IoT algorithms to run on tiny microcontrollers, but we use powerful server clusters for machine learning. The truth is that in both cases, we are asking the system to process way more information than it can easily deal with.

A microcontroller might buckle under the weight of a few iPhone images, but even a beefy GPU will struggle with today’s deep learning workloads. Applications are straining devices to the limit, but we can’t just wait for better hardware - Moore’s Law is on life support, and application-specific computers are expensive. It’s clear that we need to make better use of the resources we have.

Cue the clever algorithms.

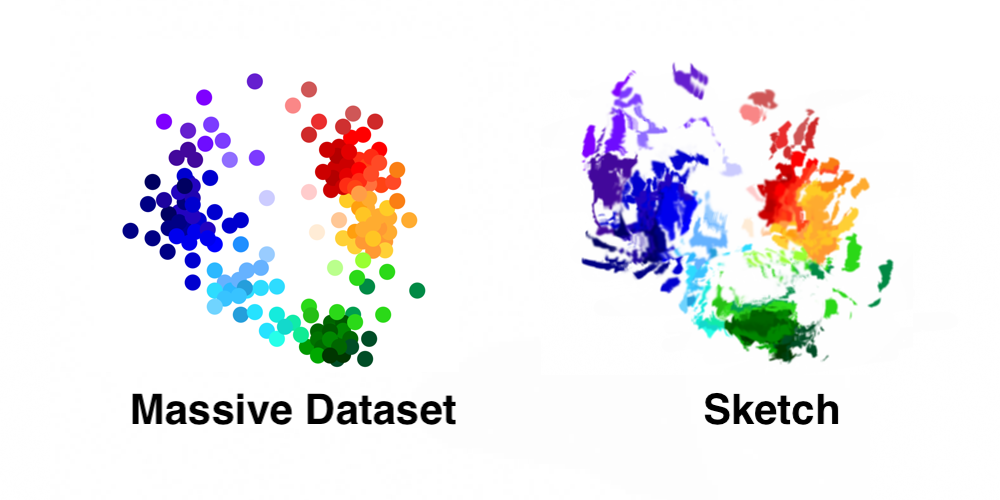

1. Data Sketches

Sketching algorithms are designed to turn massive datasets into a tiny summary. That summary is called a sketch, and it’s often much smaller than the original dataset. Sketches save time because they throw away small details that you might not need to process, while keeping the high-level features of your data. Precision is a resource, and sketches trade precise answers for efficiency.

Sketching algorithms are like ultralight airplanes.

Normal planes cost millions of dollars. Ultralight planes cost about $10k.

Normal planes need tons of infrastructure. Ultralight planes need a small garage.

Normal planes have comfortable seats. Ultralight planes have open cockpits.

But if you’re taking aerial photographs, you’ll get the same view from an ultralight as you would from a private jet. Sketching algorithms will give you the same big-picture insights that you would get from an exact approach with expensive hardware, but at a much lower cost. The downside is that there might not be a sketch that can do the kind of analysis you need. Just as the goal of an ultralight plane is to get you airborne without any extra features, most sketches can only answer one specific kind of question.

Here is a (non-exhaustive) list of questions that we can answer:

- Bloom Filters: Ask whether the dataset contains a particular object

- Count Min Sketch: Identify the most common objects in a dataset

- HyperLogLog: Estimate the number of unique items

- RACE Sketch: Approximate the probability density of the dataset

- STORM Sketch: Train linear regression and classification models

It pays to develop some intuition for these sketching algorithms before deploying them in production. Most sketches have a mathematical theory that describes the balance between computation, memory and precision. Once you know the tradeoffs, you can see some crazy performance numbers. For example, we have used Bloom filters to index 170 TB of genetic data in 14 hours, and we use the RACE sketch to filter thousands of metagenomic sequences per second.

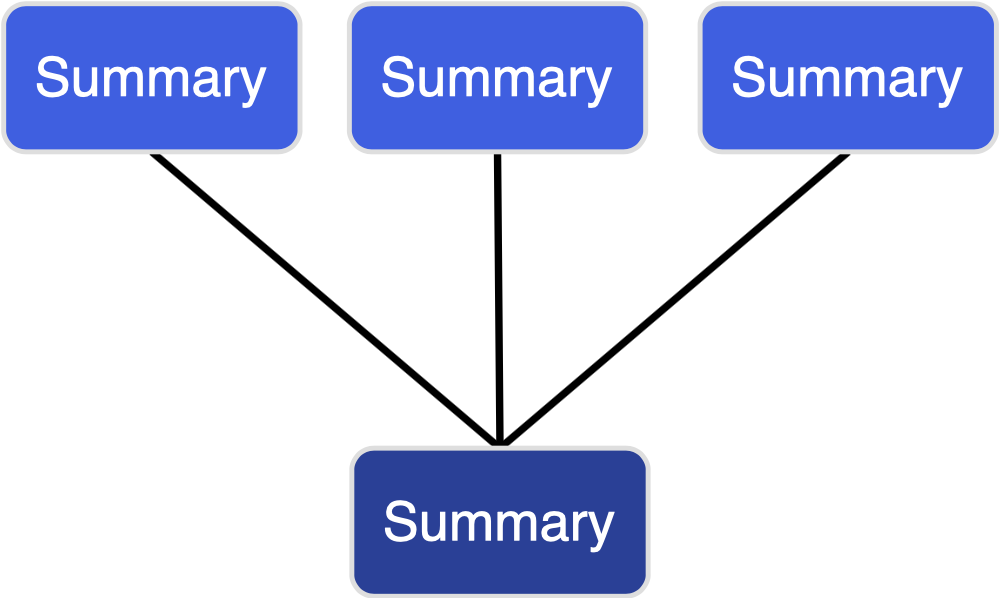

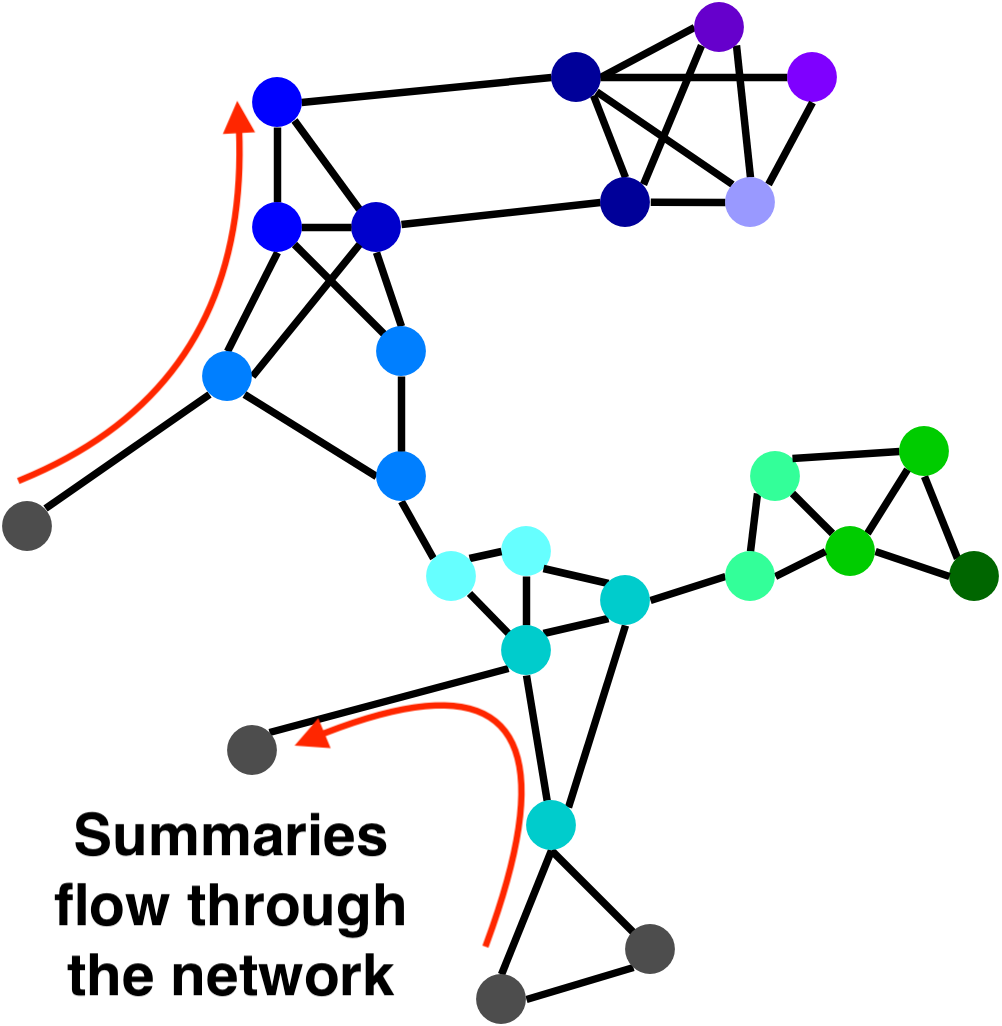

2. Mergeable Summaries

Mergeable summaries are ideal for distributed systems where data is collected or stored on multiple devices. A summary is mergeable if we can combine two small summaries so that their combination represents the contents of both datasets. The merged summary should be roughly the same size as the original, otherwise we could simply stack the two summaries on top of each other.

Mergeable summaries are important for parallelism and communication. Most sketches are mergeable, and some - such as the Count Min Sketch - even support an “undo operation” that can remove a component from the merged summary. This is powerful for IoT because connected sensors can transmit summaries of local data through the IoT network. To analyze big data, we can partition a massive dataset onto a network of computing nodes. Each node summarizes its part of the dataset, then merges with its neighbors. The merging property allows us to aggregate the summaries along the connections in a network without centralized control.

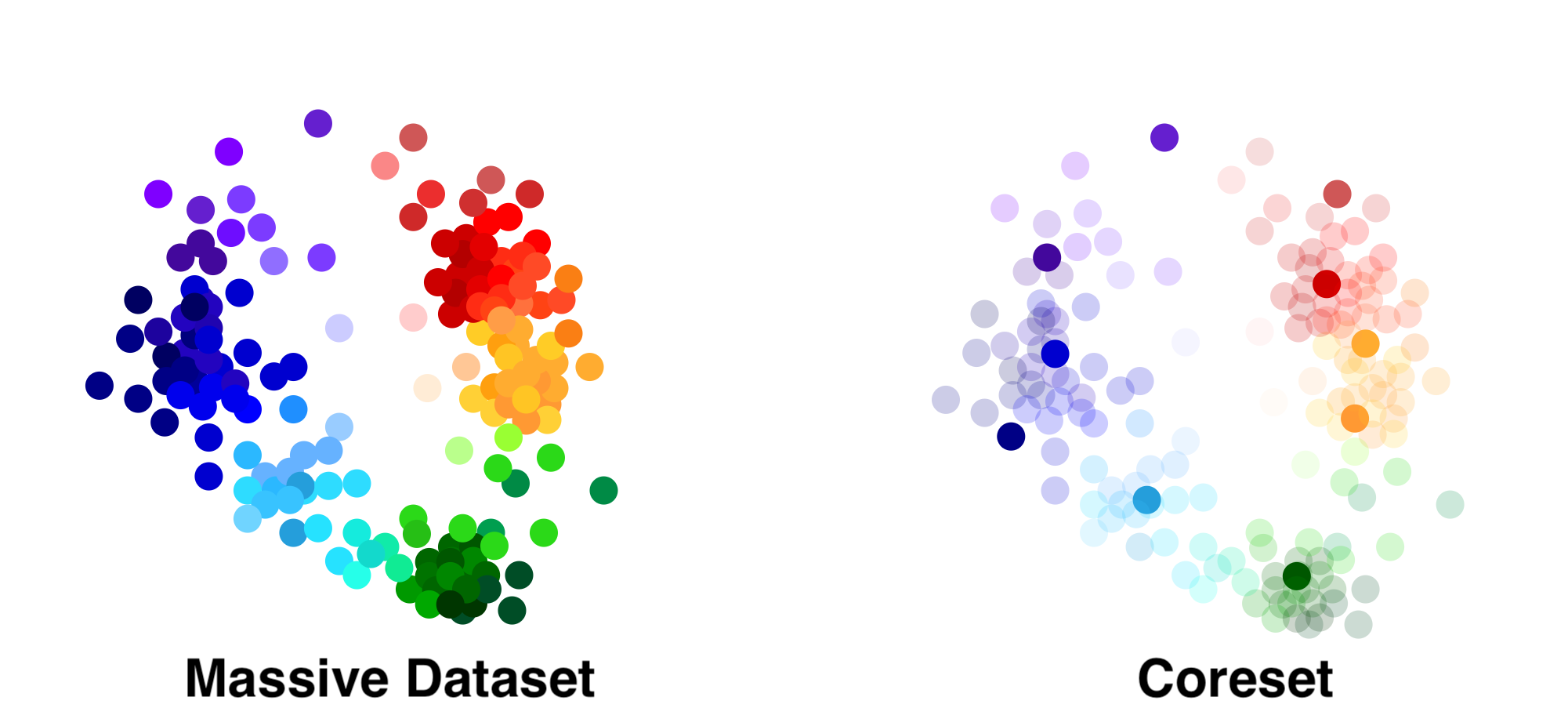

3. Coresets

A coreset is a “core set” of points that do a good job of summarizing the dataset for a particular task. Constructing a coreset is like highlighting a textbook - you keep the parts with the most information and toss the redundant or unnecessary parts.

The coreset in the picture consists of the dark points, which were selected from the massive dataset. Some coresets are also made of synthetic points that are not necessarily present in the original dataset. Sometimes, we also associate a weight with each point - “important” points get larger weights.

Coresets are smaller than the original dataset, so they are easier to process. At the same time, they have strong theoretical guarantees for learning problems. This means that coresets will always produce a good model, as long as the original dataset trained a good model. For example, if you use a coreset for linear regression, the regression line will be within a small tolerance of the line you would get from the full dataset.

Like sketches, coresets are not one-size-fits-all. A coreset for linear regression won’t perform well for logistic regression. Fortunately, there are known coresets for many problems, and more are being discovered all the time. There is also a push toward mergeable (or composeable) coresets that are efficient to construct.

As far as I can tell, the end goal of coreset research is to discover a small coreset for every technique in statistical machine learning. We already have good coreset algorithms for linear regression, logistic regression, k-means clustering and more. This is an active research area, but there will be large implications for IoT and big data as cutting-edge coreset methods become more mainstream.

Conclusion

We talked about three scaling tricks for machine learning. Coresets reduce the amount of data you need to process, while sketches compress information into a tiny data structure. Both methods support merging tricks to parallelize your application and reduce communication costs. On their own, each of these tricks can dramatically reduce your computation costs. Together, they can push today’s hardware to its limit and solve problems that aren’t otherwise tractable.

[Photo Credit] NASA on Unsplash

[Photo Credit] Zhenyu Ye on Unsplash